Revisiting Chicken Scarpariello

May 28th, 2010As we prepare the manuscript and ebook formats of our culinary history and cookbook, Almost Italian, we are rephotographing some of our creations. While we’ve spent three years looking into the rear-view mirror of our 1956 De Soto as we blogged about the evolution of Italian food in America, photography has raced ahead. Digital photography has enjoyed advances that would dazzle those paisani disembarking in New Orleans, New York, Providence and Boston to pose stiffly for their first black-and-white photos on American shores.

Photo Copyright © 2010, Skip Lombardi

One dish that merited a retake was Chicken Scarpariello, Chicken Shoemaker-style; and so we made it again last night. But because it was so hot last evening, still in the high 80’s, we grilled the chicken rather than giving it the traditional stove-top braise. The palmetto-smoke infused both chicken and sausage, adding one more dimension to an already zippy dish.

For this new photo, we served our chicken and sausages on a bed of capellini, rapidly cooked just short of al dente, before we swirled it into the pan-sauce.

Since Memorial Day Weekend is the official start of the outdoor grilling season, we encourage you to try this variation of the Italian-American classic.

Photo Copyright © 2010, Skip Lombardi

Follow the Chicken Scarpariello recipe on AlmostItalian.com with these small changes:

• In a large frying pan on the stove, sauté the onions, garlic and red pepper flakes. Cut the cooked sausage into rounds and slide them and the grilled chicken into the pan. Add the wine and proceed with the rest of the recipe.

You can make the dish ahead and cook the pasta just before serving.

Any Knights of Columbus marching this Memorial Day will toss of their capes, doff their plumed hats to you, and be very happy to find this on the picnic table after the parade!

The New Portuguese Table

May 9th, 2010When I lived in Portugal, it was not yet a member of the European Union. USAID still had a Lisbon office because, even in the 1980’s, Portugal’s economic development lagged far behind the rest of Western Europe and the nation met criteria for American aid.

Despite decades of northern European and British tourists seeking sun of the shores of the Algarve province, Portugal’s cooking was conservative, and I mean that in a positive way.

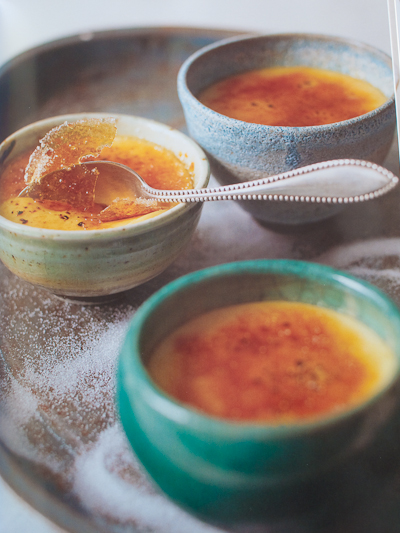

Photo Credit: Nuno Correia from The New Portuguese Table

Cooks were fiercely self-confident and their dishes regionally distinct. The country’s legions of farmers and shepherds as well as its coastal Atlantic fishing fleet made most Portuguese locavores by default. The words “nouvelle cuisine” had not yet been whispered in Lisbon, where culinary fusion (circa 1985) meant that medieval Moorish recipes for marzipan and candied egg yolks might incorporate chocolate from Portugal’s former colonial plantations in Brazil or Angola. French influence was present, but only in the kitchens of the old aristocracy or chandeliered restaurants where London wine importers lunched with Lisbon bankers. Techniques and sauces of the ancien regime français had arrived with bayonets, when Napoleon’s armies overran the vineyards and groves of olives, citrus, and stone fruits surrounding Portugal’s quintas, the grand country estates.

But like David Leite, whose southern New England turf I’ve shared, I first knew a very different kind of Portuguese culinary world, that of the Portuguese-American diaspora, largely from the Azores, Portugal’s mid-Atlantic islands. Azorean mariners had settled amongst earlier immigrants—the Germans, Irish, Italians, and Slavs of New England ports and mill towns. They founded their largest enclaves in Massachusetts and Rhode Island and their struggles and success, like those of all new American immigrants, would be reflected in the food and drink of celebration, homesickness, and consolation.

It was a world of boisterous relatives crowded into kitchens that the adolescent David Leite, wishing to be reborn as a WASP, tried to escape. Fortunately maturity and the flood of culinary nostalgia that can overtake us as we contemplate the inevitable loss of beloved elders pushed him to reexamine his cultural identity. He set about to gather recipes from his mother and grandmother.

Then Mr. Leite embarked, not just for the Azores (his parents’ birthplace), but also for Iberian Portugal, to discover that the 1950’s Kodachrome postcard-views, his family’s recollections, had faded. By the 1990’s, Portugal, that once-charming backwater, had become a full-fledged member of the European Community. As Mr. Leite dined with urbane friends immersed in the sophisticated and rapidly changing gastronomic offerings of Lisbon, he was astute enough to realize that he must “embrace this meal, this dining scene, this Portugal.” More importantly, he recognized that, in doing so, he was not “betraying” his family.

Most of the recipes of The New Portuguese Table have antecedents in typical Portuguese home-cooking, but Mr. Leite may use duck breast (rather than the whole bird) or give instructions to braise, rather than to fry in lard. He gives the nod to modern equipment like immersion blenders. Portugal’s cooks at both the home and restaurant levels are reaching into the global pantry and embracing more culinary influences from Portugal’s former colonies in Africa and Asia. Ingredients like fresh ginger, bird’s-eye chilies, and star anise show up frequently.

Frango Naufragado, Shipwrecked Chicken, is a vagabond that supposedly made its way from Mozambique to Chinese Macau via Goa before showing up in Portugal. Whatever the back-story, it’s delicious: grilled chicken meets coconut milk tomato paste, lemons, and chives. Fusion is now the operative word.

Mr. Leite gives us some real curiosities, including an old recipe for Licor de Leite. The liqueur may have a dual heritage in both the distillation techniques perfected by teatotalling Arabs and in the infused digestives concocted by cloistered Catholic orders.

But for those who simply want to recreate flavors from a honeymoon trip to Faro, Cascais, or Nantucket—Mr. Leite has some old favorites like Caldo Verde (Kale Soup) and Lulas Recheadas (Stuffed Squid). Meanwhile, he and his collaborators have created new dishes with staple ingredients—chouriço bread, fava bean salad, cilantro pesto, crème brulée infused with rosemary, and what can be legitimately described as a salt-cod slider or bacalhau burger.

The author acknowledges that “dishes… put in front of me by the women who love me” are the true foundations of the book. David Leite honors those old ways as he gives his readers new ways to capture and enjoy the distinctive flavors of classic and modern Portuguese cooking.

The New Portuguese Table is embellished with the work of photographer Nuno Correia and a team of food stylists and prop finders. Their efforts exemplify fine cookbook illustration and perfectly express the essence of Portuguese food.

The New Portuguese Table:

Exciting Flavors from Europe’s Western Coast

David Leite

Clarkson Potter (August 18, 2009); 256 pages; $32.50

Cookbook Review: Steamy Kitchen

April 29th, 2010A few weeks ago, we asked the question: Do Cookbooks Matter?

To some of us—cooks, culinary writers, photographers, food stylists, graphic designers, publishers—these books are part of our livelihood. To the vast number of people who dream of wearing one of those food-career labels, cookbooks are escapes from a world in which meals are mostly grabbed on the run by those who too rarely participate in either cooking or dining with others.

Mom’s Chinese Steamed Fish from The Steamy Kitchen Cookbook

Photo by Jaden Hair

We’d contend that viewers watch Food TV more to be with entertaining “food people” than they do to learn how Paula Deen mixes meatloaf or Ina Garten whips cream. Whether pictures of the geeky Lee Brothers and their friends cracking crabs at a Low Country picnic are in a book or a magazine, to see the photos invites us to suspend reality and to temporarily share that camaraderie—even if all we are contemplating for a solo dinner is diet soda and half a cup of cottage cheese .

When it comes to cookbooks, picture-perfect presentations of artisan loaves, rustic faience platters beneath glazed roasts, exotic table textiles, candles, and wildflower bouquets (all expertly captured by the camera) are part of the allure. But in the age of Facebook and “friends” one may never meet—it’s often the images of people, guests enjoying themselves around food celebrities, that allow us to share the hipness and happiness so much harder to achieve in our real lives.

And while millions of these photos (not to mention thousands of cooking videos) can be seen on the Internet, cookbooks remain a way to remove ourselves from the world-view filtered by search engines. For better or worse, screen-delivered content is part of our lives. Whether we are lucky enough to still claim a job in a cubicle or are stuck at home, spending hours on Monster.com searching for jobs that would land us back in a cubicle, a lot of us live online. That’s one reason it’s soothing to read something on that material created by the ancient Egyptians—paper.

Continuing to examine and cook from the new books piled high in our dining room, today we look at someone whose trajectory we’ve been following for a few years:

Jaden Hair began Steamy Kitchen as a blog and expanded it into a successful cookbook that is testimony to both the realities of everyday life and the social rewards of sharing food. Chinese-American and raised by a mother who cooked, the author didn’t learn her craft at her mother’s wok, but fired up her own only when she became a homemaker and mother of two boys.

In brief—although a few of her offerings are classic Chinese (Mom’s Chinese Steamed Fish), most of Steamy Kitchen’s recipes are what we’d call fusion food or “Asian Modern” (Furikake French Fries, Pork & Mango Potstickers, Thai-style Chicken Flatbread, Asian Pear Frozen Yogurt). Jaden uses straightforward techniques, fresh ingredients, and some Asian pantry staples to yield brightly flavored dishes. Her stance is that authentic tastes and textures of Chinese, Thai, Vietnamese, Korean, Malaysian, and Japanese food can be readily achieved by home cooks willing to invest a little time and thought in a week-night family dinner.

Clearly, the Steamy Kitchen blog readers, scores of whom volunteered to test recipes for the cookbook, find food conversation stimulating; it adds another dimension to their social networking. Jaden-the-blogger has made her readers feel like friends around the table and has built an enormous following thanks to her seductive photography and casual, let-me-tell-you-a-secret monologue. Her telegenic appearance and personality haven’t hurt, either. But most significantly, Jaden’s recipes are for dishes readers want to make and share.

Jaden’s got it right—if you’ve read the recipe, assembled your mise en place, and follow her instructions—it won’t take much time to prepare a delicious meal, one that will surpass anything you could order in most Asian restaurants in America.

The most striking aspect of The Steamy Kitchen Cookbook is the spectacular food photography. Self-taught and dauntless, Jaden-the-photographer managed to persuade Tuttle, her publisher, to let her do almost all the photography for the book. Given how far Tuttle went to feature a color picture of every dish, some bigger than life-size, one wonders why the handful of instructional photos (not taken by the author) weren’t given a little more space.

As one reader described it, Steamy Kitchen is “text-dense.” In addition to recipes, the book is packed with anecdotes, family memories, and copious credits to friends and fellow-foodies. What should not have been given so much real estate is the sophomoric, bloggy chatter, some of it trite and off-color. It’s a glaring distraction from the simple elegance of the recipes and illustrations. For their own sake and that of a first-time author, we wish Tuttle’s editors had asserted themselves at least as much as Jaden’s garlicky Asian Pesto.

Nonetheless, Jaden’s suggestion of using a Microplane to grate those devilishly hard lemongrass stalks gains her redemption. The text can be cleaned up for the second edition. For now, we’ll forgive her and wish her the success she deserves.

The Steamy Kitchen Cookbook:

101 Asian Recipes Simple Enough for Tonight’s Dinner

Jaden Hair

Tuttle Publishing (October 10, 2009); 160 pages; $27.95

Turkish Loquat Kebab

April 11th, 2010If you live anywhere in Florida, as far to the north as US Dept of Agriculture Zone 7, you can see Eriobtrya japonica, loquat trees, beautiful broad-leafed evergreens native to Japan and China. If you are in the Carolinas, your loquats may be purely decorative shade specimens that rarely bear fruit. But here in Florida, we are especially lucky this year; even after some serious freezes, the 2010 loquat “crop,” at its peak right now, is the best we’ve seen in years. The small, oval fruits range from pale green to the color of apricots, when they are ripe.

Copyright © 2010, Skip Lombardi

To the unfamiliar, ripe loquats look a lot like queen palm fruits, which are falling to the ground now. But once you see loquats against their tree’s distinctively veined and fuzzy leaves, there’s not chance of confusion. Palm trees look nothing like loquats!

People in my part of the world, the Mediterranean and the Middle East, love loquats, which are often misidentified by tourists as medlars, a different, northern fruit that is rarely cultivated in North America. Nonetheless, medlars and loquats are both members of Rosaceae, the Rose family—along with all the stone-fruits, quinces, apples, and pears. (Known as nespre and nespoli in France and Italy, the Turkish names for loquats translate as “Malta plums” or simply “New World,” odd tags for fruit from the Far East.)

Turks cannot enjoy loquats quite so early as Floridians. They come into the Istanbul and Ankara markets in May, along with strawberries. Restaurants will offer diners platters of fresh strawberries and loquats, and one could certainly do that here in Florida this year. Although mature loquats shade yards and streets throughout older Florida neighborhoods, very few residents seem to realize that loquats are edible. We continue to be amazed that so many delicacies go unharvested here. Perhaps we should call this post Florida Foraging 202…

Human ignorance is the birds’ and squirrels’ gain. Many a fruit will have a tiny peck from a jay or mocking-bird. (That’s one way to be sure they’re ripe! They are still safe to eat.) And if the fruit have already fallen to the ground and are a bit bruised, but intact, don’t discard them. Fruit soft enough to bruise will be sweet.) Just rinse them off and pit them; most have one or two shiny brown seeds that you can quickly and easily remove with your fingers. Enjoy loquats fresh, in salads, or—as the Turks do—briefly cooked in meat dishes.

Copyright © 2010, Skip Lombardi

This is hardly nouvelle cuisine. The combination of fruit with meat has roots in the pre-Islamic cooking of ancient Iran. When Islam came to Iran in the seventh century AD, it quickly appropriated the sophisticated cuisine of the Persian elite, who had long cultivated fruits indigenous to Mesopotamia and more distant regions of Asia. The spread of Islam and its willingness to incorporate non-Arab customs meant that, within a few centuries, Persian cooking styles were known from Central Asia and Northern India to the entire Mediterranean and beyond–as far as the Atlantic shores of Portugal and Morocco. Today, many of Morocco’s complex dishes of meat slowly cooked with tart fruit (whose acidity acts to tenderize the meat) are strikingly similar to creations that would have been served in ancient Persia.

The juncture of agricultural richness and continued cultural interchanges between northern Syria and southeastern Turkey have helped maintain many unique regional dishes that still whisper the influence of Persia.

In the Turkish province of Gaziantep along the Syrian border, loquats and lamb come together in an easily made dish with flavors as complex and beguiling as the region itself. Here is one version of the regional treat known as Yeni Dünya Kebabi.

Turkish Loquat Kebab (YENI DÜNYA KEBABI)

Such entertaining confusion just seems to be an everyday seasoning in this part of the world, as highlighted by the old song, It’s Istanbul, not Constantinople.

Ingredients:

6 ounces brown or green lentils

8 ounces ground lamb (leg or shoulder meat)

1 medium yellow onion

2 cloves of garlic

2 tsp minced fresh ginger

Italian flat-leaf parsley (enough to yield at least 1/2 cup when minced)

1 tsp freshly ground black pepper

1 tsp freshly ground allspice

1 tsp cinnamon

2 tsp dried oregano

2 tsp sweet paprika

1-2 tsp red chili flakes, to taste*

1 Egg, beaten

1/3 to 1/2 cup fine, dry bread breadcrumbs (commercial are OK)

Salt to taste

At least 20 loquats, as many as 40

1 Tablespoon pomegranate concentrate (nar pekmez in Turkish)

or ordinary balsamic vinegar

Fresh spearmint– chopped & sprigs for garnish

*(or Turkish Antep, Urfa or (Syrian) Aleppo pepper– any sweet-hot pepper you like)

Preparation:

Inspect the lentils, removing any debris. Rinse and bring them to a rapid boil in 1 1/2 cups of water in a small saucepan. Turn off the heat and cover the pan. Set it aside.

Pit the loquats and break or cut each into 2-3 pieces. Refrigerate.

Organize all the other ingredients.

In a food processor, mince the ginger, garlic, and onion. Scrape them all into a 2-quart mixing bowl.

Mince the parsley (stems and all) and add to the bowl, along with the ground lamb, egg, and all the seasonings. With a spoon or spatula stir them to combine.

Check the lentils; they will have absorbed most of the water and should be almost done, with some resistance when you bite one. Drain them, reserving any liquid.

Pulse lentils in the food processor a few times, to break them up.

Stir the lentils into the meat mixture. Add the bread crumbs, more or less, depending on how wet or dry the mixture seems to be. You want to be able to form 16-20 oval meat patties (köfte, in Turkish), each about 2 inches long. Köfte may be made up to 24 hours before finishing the dish.

In a large non-stick skillet, 12-14 inches, sauté the köfte over medium heat. Allow them to brown for 5-7 minutes on one side before turning them (this parcooks them and makes them easier to turn. Turn the köfte, and as you are browning them, add the reserved loquats to the pan. If anything begins to stick, add any of the reserved lentil broth or a little water. When the meat is browned and the loquats have started to soften, drizzle the pomegranate concentrate or balsamic vinegar over the köfte.

Serve the köfte and any pan juices with white rice or bulgur pilav. Sprinkle each portion with freshly snipped mint and garnish with a sprig of mint.

For details on loquat cultivation see the excellent botanical website: http://www.floridata.com/ref/e/eriobot.cfm