Remembering Dave Brubeck

December 6th, 2012I‘ve been a Dave Brubeck fan for more than 50 years. Although I knew him only through his concerts and recordings, the news of his death yesterday struck me like the loss of a dear, old friend.

Photo Credit: Richard Avedon

I had an uncle—an ardent Jazz fan—who always seemed to have a new recording with him each time he visited. By the time I first heard Dave Brubeck in 1954 or ’55, I was already familiar with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and the rest of the mostly black, New York-based, Hard Bop Jazz players. Even though I was only eight years old, I had, thanks to my uncle, developed a good basis for comparison of their different styles.

Dave Brubeck was considered to be a “West Coast” musician: a member of the “Cool School” of Jazz. And indeed, his music—particularly with Paul Desmond on alto saxophone—lacked the edge and drive that typified the “East Coast” be-bop of the day. But he and his quartet played with élan, facility, brilliant contrapuntal improvisation, and previously unheard harmonies.

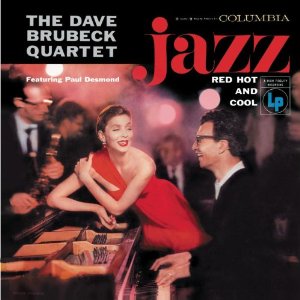

My very first Dave Brubeck album was Jazz—Red Hot and Cool. Recorded live in New York City at a nightclub called Basin Street East, it captivated me.

The album included a number of tunes considered to be part of “The Great American Songbook.” Brought up-to-date with Brubeck’s unique sense of harmony and Paul Desmond’s wonderful lyricism, their arrangements swirled above the ambient nightclub clinking of cocktail glasses.

Photo Credit: Richard Avedon

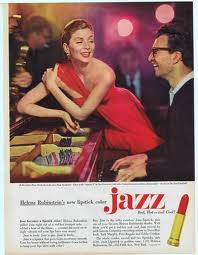

Beyond the music, that album, whose cover featured Fifties supermodel Suzy Parker and Brubeck in a nightclub, eptomized for me the coolness of Jazz. Richard Avedon—one of the premier fashion photographers of the 20th century—clicked the shutter at the hungry i, then the hippest of San Francisco’s nightspots. What many Brubeck fans have forgotten is that both Helena Rubinstein cosmetics and Columbia Records shared the same Avedon photo for their joint promotion of both the record album and Jazz, a new lipstick and nail polish color launched by Mme.Rubenstein. That interesting cross-disciplinary use of art predated Mad Men by several decades.

But my most powerful recollection is a simple four-bar modulation in the last chorus of George Gershwin’s Love Walked In. As a child, I had yet to acquire the vocabulary to describe what I heard, but all these years and an undergraduate degree in music theory and harmony later, I can easily retrofit the experience.

With twelve bars left in the tune, the group spontaneously modulated, or changed, the key of the tune, up a whole step for four measures of the final phrase before returning to the original key for the last eight measures. I had never heard anything like it and couldn’t understand it, but I felt completely drawn into the music. I have been similarly amazed by Dave Brubeck countless times since.

While I mourn his passing, I can console myself with some wonderful musical discoveries and memories, and continue to enjoy the great legacy he’s left behind. Rest in peace.