Phish Are Jumpin’

December 15th, 2009I‘ve had only one management position in my career. As “team leader” I managed four young software engineers who did quality assurance testing. Among my charges was a young fellow from Belarus who was particularly dedicated to the task; he took it personally whenever he found something wrong with the software in development.

When he found a bug, he’d come into my cube shaking his head, gravitas oozing from his pores, and say to me, “Skeeep,” before showing me his findings, “thees smells of feesh.”

I mention this because I was reminded of my young friend today when I got an e-mail—allegedly from Google—telling my my Google Adwords account had been canceled. As you might imagine, the e-mail provided no fewer than three links to my “login page,” along with helpful instructions about how to rectify this dire situation.

By now, we all know that Google hires only the best and brightest engineers in the business. And I’m certain they seek out the same capabilities in those who provide their public face through the written word. Today’s e-mail alert was not good writing.

It took very little surf-casting of my own to ascertain that the URL provided by the author of the e-mail was http://google-mc.com. A quick look at whois.net revealed that google-mc.com is registered as follows:

[Querying whois.internic.net] [Redirected to whois.melbourneit.com] [Querying whois.melbourneit.com] [whois.melbourneit.com] Domain Name.......... google-mc.com Creation Date........ 2009-12-16 Registration Date.... 2009-12-16 Expiry Date.......... 2010-12-16 Organisation Name.... denis rogers Organisation Address. 22th fireball ave Organisation Address. Organisation Address. new york city Organisation Address. 74836 Organisation Address. NY Organisation Address. UNITED STATES

As you can see, not only are the address and zip code bogus, but the registration date hasn’t yet arrived.

Putting my Web Debugger through its paces, I also found that google-mc.com eventually does hand you off to http://google.com/adwords. While this looks legitimate, be afraid… be very afraid.

So, if you get an e-mail that appears to be from Google, and if you have an Adwords account, do not follow the links in the e-mail. Instead, type http://adwords.google.com in the address bar of your browser. Even if you don’t have an Adwords account, it would be useful to forward the message to phishing@google.com. I’m sure they’ll put some of their best and brightest on the trail to seeing to it this doesn’t trouble us again.

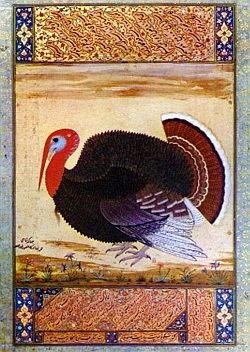

Tracking Turkey

November 23rd, 2009

apple, what might you not have done for a truffled turkey?”

In the late 18th century, shortly after the founding of the United States of America, the statesman Benjamin Franklin wrote to his daughter:

“I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the Representative of the Country; he is a Bird of bad moral Character, like those among Men who live by Sharping and Robbing, he is generally poor and often very lousy…The Turkey is a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America.” (1)

No stranger to the pleasures of the table, Ben Franklin was doubtless well acquainted with the wild turkey, a game bird indigenous to North and Central America.

In considering these birds, I would like, first of all, to deal with the English noun “turkey.” Unabashedly, I confess it to be my inspiration for this paper, which I first delivered in the country of the same name.

The most convincing etymological sources (2) speak of fowl known as “turkey cocks” in reference to large domesticated birds (provably of the genus Pavo). By mid-16th century “Guinea hens” were synonymous with “turkey-cocks” and referred to fowl of African origin. Some of these were supposed to have been brought from West Africa (Guinea) and others from Numidia via the Turkish dominions, hence the name “turkey.” Sixteenth century Spanish explorers in Mexico found that the Aztecs had domesticated a large fan-tailed bird, the huexolotl, which was prized for its meat and regularly offered as tribute to the Aztec monarch, Montezuma. The Spaniards introduced this bird to Europe, where the confusion over its name began.

For those of you who like to know the origins of words you eat, here is a brief summary of what happened to the feathered pride of the Aztecs:

The Spaniards called the new bird pavo, after the European fowls they knew.The French, considering the bird to be from the general Caribbean region called the creature poule d’Indes, or dinde, after the Caribbean islands Columbus had mistaken for India, and which we call the West Indies. Later, in provincial areas of France, the birds were sometimes known as jusites after Jesuit brothers who started a turkey farm near Bourges. (3)

Linnaeus, the great Swedish classifier, mistakenly gave the New World creature the Latin name that rightfully belonged to the Old World fowl, Meleagris gallopavo. Thus, something else (Numida meleagris) had to be concocted for the turkey-cock. (Meleagris means speckled.) (4)

The English called it turkey because it was closer in appearance to their turkey-cocks that to anything else they’d seen. The Turks, probably to agree with the French, or maybe because they thought it inappropriate to roast a creature named for their nation, chose to call the bird hindi, thus pushing matters farther east.

Meanwhile, the Portuguese preferred to go west. Sources mention that they wrongly supposed the bird to have come from Peru. To this day, Portuguese speakers from Brazil to Goa call the bird peru. And thanks to Portuguese trade with India, the Hindi name for turkey is piru.

The Arabs took their own word for cockerel, dik, and added the Arabic adjective pertaining to Turkey or Asia Minor, rumi, which referred back to the Byzantine Empire, of the Land of Rome. Thus, dik rumi, an Arab turkey, is really a Roman rooster.

But it is none other than the wild Meleagris gallopavo that American folklore has solidly established itself as one of the native foods enjoyed by the Puritan colonists of Massachusetts when they celebrated their first Thanksgiving in 1621. That feast was, by all accounts, a prayerful occasion during which the English pilgrims thanked their Savior for a safe flight from religious persecution in England and for the bounty of their first harvest in the New World.

To properly appreciate turkey’s place within the cuisine of the United States, one must look briefly at the development of our holiday commemorating the Pilgrims. As a feast-day, it was not an instant success. After that initial Pilgrim banquet, over two centuries would pass before Thanksgiving, the most “typically American” of celebrations, was officially decreed a national holiday.

Beginning in the 1820’s, Mrs. Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of an influential women’s magazine, Godey’s Lady’s Book, carried on a patriotic crusade for the establishment of Thanksgiving as a national holiday. She wrote hundreds of editorials and letters urging politicians, clergymen and the readers of her periodical to lobby for this cause. Finally, in 1863 in the midst of the American Civil War and shortly after the Northern Army’s victory at Gettysburg, the combination of Mrs. Hale’s annual exhortations and the Northern desire to celebrate its triumph prompted President Lincoln to proclaim the third Thursday in November as the national day of Thanksgiving. As early as 1857, Mrs. Hale filled the cookery pages of the November issue of Godey’s with recipes for roast turkey and other dishes to be served at the Thanksgiving meal. Despite myriad changes in food technology, taste, and society since then, American magazine and newspaper food editors still adhere to Mrs. Hale’s basic format.

Mrs. Hale and President Lincoln may have assured the seasonal demand for turkey, but so plentiful were the wild turkeys that turkey breeding for superior flesh did not attract significant commercial interest until the 20th century. Earlier American turkey breeders had concentrated on the production of large feathers deemed essential for Victorian womens’ hats and fans. (5)

While the fashion for turkey plumes may have subsided, the cooking of turkeys continued to be a subject of much discussion and divergent opinion. In “Statesmen’s Dishes and How to Cook Them” (1890), Mrs. Stephen J. Field suggested that “three days before [a turkey] is slaughtered, it should have an English walnut forced down its throat three times a day and a glass of sherry once a day. The meat will be deliciously tender and have a fine nutty flavor.” (6) An eighteenth century adventurer in the American Midwest extolled the merits of stewing a turkey in racoon fat. (7)

Currently, one highly successful processor of oven-ready turkeys advertises birds that are “self-basting.” Its raw turkeys are injected with corn oil to keep the meat from becoming too dry. Many of these turkeys are also equipped with heat-sensitive devices that indicate precisely when the bird is done to perfection.

Though its stuffings of bread-crumbs and herbs, nuts and dried fruits, sausage meat or oysters vary widely from kitchen to kitchen, a roast turkey is an essentially simple affair. It is no surprise that in the American idiom, “to talk turkey” means to speak plainly and directly, to deal with the basics. Hence one well-known firm’s “Turkey-Talk Line,” a toll-free telephone assistance service which operates from a few weeks before Thanksgiving through the Christmas-New Year holidays. Despite innovations such as birds with embedded thermometers, the firm receives thousands of calls from distraught, once-a-year turkey chefs who prove that “fool-proof” is a relative term. Panic frequently arises when a consumer has neglected to remove the bird’s plastic wrapping before placing it in the oven or has forgotten to turn the oven on until half an hour before dinner is to be served to a dozen guests.

Sentiments about Thanksgiving are strong. And since a superabundance of family members and food are what characterize the celebration for most Americans, it is not surprising that there is a collective attachment to family food traditions. This tends to discourage avant-garde experimentation. Turkeys stuffed with couscous or accompanied by a kiwi chutney do appear in magazines, but by and large, most Americans cooking for their families are unlikely to tamper with tradition at Thanksgiving. Though few would dispute the festiveness of a fine rack of lamb or a magnificent bouillabaisse, few Americans would seriously consider either suitable Thanksgiving fare. (8)

By virtue of its iconic role in the Thanksgiving dinner, turkey has become an American symbol—not so much to non-Americans, who may associate the United States with beef cattle, great grain fields, and fast food—but by Americans themselves.

Unofficially, at least, the bird with the ugly head and the spectacular plumage eventually achieved some of the status Ben Franklin begrudged the eagle. During World War II, extraordinary measures were taken to ensure that American troops overseas, and even those fighting on the front lines, were given hot turkey dinners on Thanksgiving Day. (9) & (10)

Oddly, mass popularity has not diminished wealthy or fad-following Americans’ appetite for turkey. It continues to be a meat for feasts even as improved farming has made it plentiful and cheap enough to be used instead of beef or pork scraps in sausages and hot dogs. And lean, freshly ground turkey, sold alongside ground beef in supermarkets the year round, carries no message of either Pilgrim piety or holiday largesse. More often than not, it is simply labeled “low-cholesterol.”

Despite advertising’s transformation of turkey into an inexpensive “health food,” a browned, well-basted roast turkey is in no danger of being supplanted as the centerpiece of our holiday devoted to unabashed gluttony. But what irony that the turkey (albeit stripped of its flavorful, fattening skin) should also epitomize prudent restraint for body-conscious Americans today. What would the Pilgrims think?

— Holly Chase

Notes & Bibliography

(1) The American Heritage Cookbook and Illustrated History of American

Eating and Drinking, American Heritage Publishing Co., 1964; p. 482.

(2) The Oxford English Dictionary, second edition.

(3) Larousse Gastronomique (English edition), Crown Publishers, New

York, 1964.

(4) The Oxford English Dictionary.

(5) The Thansgiving Book, by Lucille Recht Penner (Hastings House, New

York, 1996), p. 115.

(6) See note 1, p. 483

(7) The Wild Turkey: Its History & Domestication, by A.W. Schorger

(University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla; 1966, pp. 370-1). An

entertaining blend of exhaustive research and superior writing– food

scholarship at its zenith.

(8) When “new” dishes enter the Thanksgiving repertoire, food writers tend to link them to earlier American traditions. And America, at least in the geographical sense, certainly includes Mexico, source of the turkey. Yet I know of no proposals to add two especially splendid Mexican turkey recipes to the Thanksgiving table.

The first Spaniards in Mexico wrote that the Aztecs ate turkey with a sauce based on bitter chocolate, the ancestor of today’s mole poblano, a seductive poultry sauce from the Mexican state of Puebla. And then there is pavo en escabeche, stewed turkey marinated in oil, vinegar, herbs and onions—a dish with obvious Mediterranean antecedents.

(9) Thanksgiving: An American Holiday, An American History, by Diana Karter Applebaum (Facts on File Publications, New York and Bicester, England, 1985); pp. 249-250.

(10) The most typical “trimmings” would include a sage and bread stuffing, mashed potatoes, giblet gravy, cranberry relish, creamed onions and fresh celery.

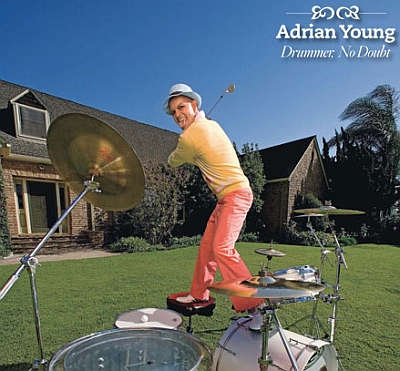

How To Get To Carnegie Hall

October 27th, 2009A few weeks ago I passed a pleasant afternoon watching the young Japanese golf pro, Ryo Ishikawa scoring one birdie after another in the President’s Cup matches. I couldn’t help thinking: “Hasn’t anyone told this kid that this game is hard?” Simultaneously, the friend with whom I was watching, said aloud “I imagine he’s done a fair amount of practicing.”

Photo courtesy Golf Digest

And of course, Ryo Ishikawa has. This young fellow was earning ten million dollars a year in endorsements during his senior year of high school.

Of course I couldn’t help thinking about my own golf game and how just a few months earlier I’d realized that I could do with a little practice myself. But that afternoon in front of the TV, I had a revelation and it was that I’ve probably forgotten more about practicing than whatever this eighteen year-old prodigy has had time to learn, even though our professional disciplines are fairways apart. As a former professional musician who’s played drums in a lot of orchestra pits on Broadway, I know a lot about practice.

Until I actually got started, though, what I hadn’t put together was that the practice regimen I’d learned over many years, most of it in cramped, poorly ventilated, sound-proof rooms, would serve me just as well under an open sky at the driving range. This summer I decided to consciously apply the principles I’d learned in music school to the re-learning of the golf swing.

Recognizing that I’d developed so many bad habits swinging a golf club that it would be too difficult to attack them one at a time, I knew I had to start from scratch. My swing needed a complete overhaul.

So I’ve drawn on my years of music study to rebuild my swing. Along the way, I’ve learned a few things:

• You cannot improve your game—even a little bit—if you don’t practice.

But the good news there is that you don’t need to spend hours—and money—at a driving range; you can practice by simply swinging a club at home. If you can find a large mirror, or a reflective sliding glass door in a safe location, you can watch yourself set up to an imaginary ball—you may be surprised at what you see—and you can swing a club endlessly on the proper swing path without ever reaching the bottom of a bucket of balls.

• You must never practice your mistakes.

How many times have you been at a driving range and watched someone beat the daylights out of fifty or a hundred balls, none of which went straight…and some of which never became airborne? You saw a pattern emerge: slice, hook, fat shot, thin shot…. The hapless duffer hadn’t swung the club the same way twice though he’d gone through an entire bucket.

Even Vladimir Horowitz didn’t get it right the first time he tried to play an unfamiliar piece of music, so how can we lesser mortals ever hope to reach a point of satisfaction? We can emulate Horowitz, who played the difficult passages at a slower tempo until he felt comfortable. You should…

• Practice your swing only as fast as you can do it correctly.

We’re way beyond the days when Ben Hogan’s Five Lessons was the definitive statement about the golf swing (and back then woods were indeed made from wood). Today the Internet is a treasure trove of golf education. If you want to address the ball properly, Tiger’s swing coach, Hank Haney, is online and will teach you—free of charge. Want to develop a wide back-swing like Davis Love III’s? David Ledbetter will show you how. You can spend hours watching Ernie Els, Vijay Singh, and Fred Couples hit them over the moon with what appears to be no effort at all, but eventually YOU need to put down the remote and get of the sofa to practice. And you must do it correctly.

So like Vladimir Horowitz when he had to tackle a difficult passage, you must slow down to the point at which you can get it right. And you must repeat the correct motions over and over until they are automatic, until you are no longer able to do it incorrectly. You didn’t acquire those bad habits overnight, and you may even have compensated for your slice or hook to be able to play reasonably well. But starting over and adhering to slow, methodical practice—in tempo and free of tension—will pay handsome rewards when you take it back to the golf course.

• Practice in tempo.

Even a musical speed-demon like Lang Lang needs to go slowly the first time he sight-reads a new piece of music. But he’ll do it in tempo and “work it up.” This is as applicable to golf as it is to the piano.

A good golf swing has a clear and distinct tempo. As you go about your practice routine, be mindful of your own rhythm. Again, Ernie Els and Fred Couples look positively lazy when they swing a golf club but each has his own clearly discernible tempo. Arnold Palmer and Lee Trevino used to yank the club back and lunge through the ball faster than the blink of an eye but they, too, did it in tempo.

Some instructors suggest counting, “one-thousand-one, one-thousand-two, one-thousand-three,” with “one” being the start of the backswing and “three” being the moment of impact. Some recommend humming throughout the swing, while others suggest inhaling deeply on the backswing and exhaling through the mouth on the downswing. Just remember, if at any point your breathing isn’t smooth, you’re slipping out of tempo.

• You must free your body of tension.

When Jack Nicklaus was taking the golf world by storm, a sportswriter clumsily declared that the golfer was a “Power Hitter.” Certainly Mr. Nicklaus was very fit and athletic, but power in the golf swing derives from the coordinated turning of the hips, torso, and shoulders to develop clubhead speed. Golf is not a game of power but, rather, of centrifugal force.

So if you’re gripping the club too tightly, or trying to hit the ball with the power of your arms, you’re creating tension and sacrificing clubhead speed.

One of the best drills I’ve found for taking a relaxed swing is called the “half swing,” or “nine to three” drill. (Dave Pelz extolls the virtue of the “nine o’clock swing” for wedge play, too.)

Assume your normal stance to address the ball. Then, turning your shoulders and maintaining a very light grip on the club, bring the club back so that your arms are parallel to the ground (9 on a clock face). Next, hinge your wrists upward so the club is perpendicular to the ground.

When you’ve reached 9 o’clock, turn your shoulders back, let your arms fall through and swing back so your arms are parallel to the ground on the opposite side of your body (3 on a clock face). Now, hinge the wrists again so the club is perpendicular to the ground. Note that most of your weight should now be on your outside foot.

It’s a lot to keep in mind, so if you feel any tension at any point in this exercise, slow down—but stay in tempo. Just relax and feel the centrifugal force of the clubhead.

As you continue to do this exercise you’ll discover some amazing things: Your body—without any coaching—begins to move exactly as it should, limbs and weight moving in exactly the proper sequence. On the backswing, you’ll feel your weight transfer naturally to your back foot. On the downswing, you’ll feel your shoulders turn just when they should, and you’ll arrive at the finish position in perfect balance with most of your weight on your outside foot. Remarkable. Do this exercise for about five minutes per day and you’ll experience some wonderful results.

If they’re anything like mine, you’ll discover that you’ve stopped hitting the ball fat or thin. You’ll derive a quiet satisfaction from hitting crisp iron shots. Your ball will be on the green (or at least in the same zipcode) in two or three shots—instead of five or six. With each round, your passion for the game will only increase.

Of course, there is that tawdry business about your short game, but take your successes as they come. One side benefit of practice is that you’ll develop an appreciation for the touring pros whose post-match assessments are reminiscent of Alan Greenspan’s statements on the economy. Even if you never understood Greenspeak, you’ll know what a golf pro means when he says, “My score didn’t reflect the quality of my shotmaking today”

But you will be a better golfer.

Kimchi Confidential

October 7th, 2009Update: October 6, 2010. Today, on their popular Morning Edition broadcast, National Public Radio featured news of a kimchi crisis. NPR’s Asia correspondent reported a serious kimchi shortfall in South Korea– due to a poor harvest season for the requisite Napa cabbage. Our comment ten months ago (see below) that “kimchi…is inexpensive to make…” still holds true for us in North America. Meanwhile, inside Korea, this staple food has soared in price .

Listen here to learn about Koreans’ passion for kimchi, and the sacrifices they’ll make to continue to enjoy South Korea’s national side-dish.

Google KIMCHI, KIMCH’i or KIMCHEE and you’ll not only get recipes for what you thought was merely a pickle, but you’ll learn a lot about how a people defines its national culture through food. The countries of North and South Korea are certainly divided on many issues, but no one disputes that pungent force which is a shared love of kimchi.

Photo Copyright © 2009, Skip Lombardi

So why, aside from the fact that the most widely-known kimchi sports our holiday colors of red, white, and green, are we writing about kimchi now, two days before Christmas?

Need an almost last-minute gift for the gastronomes on your holiday list?

Slightly fermented Napa cabbage kimchi, not only packs a punch, but it’s quick and inexpensive to make. And at this chilly time of year, even in Florida, you don’t have devote precious refrigerator real estate to shelving it. Just make it and deliver to your lucky recipients. (Then THEY can find a cool place to store it, if they don’t devour it within a day or two.)

So, what if you have NO TIME AT ALL? This staple of any Korean pantry can be bought fresh from our local Korean shop in Gulf Gate. Better still, the shop sells everything—including the cabbage—that you need to make kimchi yourself, so that you can adjust the levels of salt, fermentation and chili-heat, as well as the other seasonings, to suit your own taste. If you do make it yourself, just be sure you allow at least 12 hours to wilt the cabbage before you intend to pack it into jars.

Kimchi can be made from scores of different vegetables, fruits, wild greens, and even seafood. Online, you’ll discover hundreds of recipes—in English, Korean, and several other languages.

Today, we offer our very basic kimchi simply as an antidote to all the sweet gift food that floods our larders in late December:

Napa Cabbage KIMCHI

One large head of Napa cabbage (approximately 4 pounds)

Salt (at least 1/2 cup)

8 kumquats or 1 large lemon (optional)

1/4 lb fresh, firm ginger-root

4 scallions (including green tops)

6 cloves of garlic, sliced lengthwise in thirds

2-3 Tbsp Asian fish sauce (such as nuoc mam)

1/2 tsp dark sesame oil (optional; it adds a smoky flavor)

1/4-1/2 Cup Korean-style coarse red pepper flakes; medium heat (or to taste)

Remove and rinse any loose, outer leaves from the head of cabbage. Squeeze them out and pat them dry with a kitchen towel. Trim off and discard any discolored parts of the leaves or the full head. With a large, sharp knife or cleaver, cut the loose leaves into large pieces and quarter the entire Napa head lengthwise. Cut each quarter across into thirds.

Separate the leaf chunks into a very large, non-reactive bowl and mix with the salt—by hand or with 2 wooden spoons—so that each piece of leaf has a gritty coating of salt. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap and let it sit in a cool place for at least 12 hours.

Assemble a few large, clean, lidded glass jars and a roll of plastic cling-wrap.

Uncover the bowl. The leaves should be wilted and greatly reduced in volume. Pour off and reserve any accumulated liquid. Take handfuls of the leaves and squeeze them to release more liquid. Pour that off and add to the reserved liquid.

Slice the kumquats in half and remove the seeds.

If using a lemon, remove any seeds and slice into thin half-moons.

Julienne the scallions into match-stick lengths.

Rinse and slice the ginger into dime-sized pieces (no need to peel it).

Toss the sliced garlic with all the ingredients above and then add the chili pepper and a few drops of sesame oil. Toss the leaves so that they are evenly coated with the chili flakes.

Using a pair of tongs, begin to pack a jar with the leaves, pressing them in so that there is little room for air. For aesthetics, try to put a a few pieces of kumquat or lemon and the brighter green leaves and scallion tops towards the outside of the jar. Pack the jar firmly with cabbage to within 1/2 inch of the top. Repeat with another jar until you have used all the cabbage mixture.

Taste the reserved salty water poured off the wilted cabbage. If you find it pleasantly salty and a little tangy, great; you can use it as it is. If it is unpleasantly salty, dilute with up to one third plain cold water until YOU like the taste. Now, pour some of this liquid back into each jar, pressing down the cabbage to release any air pockets.Be sure that all the contents are covered with liquid and nothing is floating to the top of any jar.

Cut a double square of plastic wrap and place it over the jar opening so that it covers it completely and extends an inch beyond. Place lid over the plastic wrap and secure tighly. ( If you need an instant hostess gift, you could give the kimchi away at this point, but it is better to wait another 12-36 hours.) Read on….

Put the jars on a non-reactive tray or plate and let them sit at room temperature for at least 12 hours. The contents will begin to ferment and the liquid may rise and leak from the top of the jars, collecting on the tray. If the smell bothers you, simply rinse off the jars and tray as the liquid collects. After 24 hours, open one jar and remove a little of the cabbage to taste. If you like what you have, slow down the fermentation by refrigerating the jars. (It’s a good idea to keep a saucer under each as long as the jar is full.) If you prefer a more sour flavor, allow the fermentation to continue at room temperature. Keep tasting until you reach a balance of salty and sour that pleases you, then refrigerate the pickle.

Serve as a condiment with grilled poultry or meat. A few spoonfuls of kimchi will transform a bowl of steamed rice or Asian noodles.