Adventures of an Italian Food Lover

August 30th, 2007

Adventures of an Italian Food Lover

With Recipes from 254 of my Best Friends

Faith Willinger

Clarkson Potter (July 10, 2007); 256 pages; $32.50

We wouldn’t mind starting our days the way Faith Willinger does—coffee at the Santo Spirito market in Florence before a stroll over to the open air produce section to chat with friends about ricotta salata or le primizie, the earliest of spring vegetables, or simply to inquire, “what’s good today?”

The conversation continues in Adventures of an Italian Food Lover, Ms. Willinger’s assemblage of 107 recipes “from 252 of her best friends.” Much of the book is devoted to brief profiles of an eclectic and entertaining group of restaurateurs; caffè owners; and artisans producing pasta, cheese, wine, grappa, vinegar, and gelato. These characters, including, the inventor of pescaturismo, charter fishing vacations in Italy, shine just as brightly as her more notable companions: Arrigo Cipriani, owner of Harry’s Bar; Dario Cecchini, the flamboyant Tuscan butcher known for quoting Dante to his customers; and Fabio Picchi, culinary rock-star chef and owner of Cibreo in Florence.

But famous or not, Ms. Willinger’s friends are no slouches. Virtually every one of them has chosen food as a vocation, and all have secured a place in Ms. Willinger’s heart. Thoughtfully, she includes the names of their businesses, hours of operation, addresses, telephone numbers, e-mail and web sites alongside the profiles. The book is as much memoir as Italian food compendium. But as cooks and travelers, we wish that the wealth of information within these pages were organized in a more conventional and accessible manner—with a complete table of contents and an index listing the personalities and their establishments.

This album of gastronomic personalities, is divided into three main sections: North & Central Italy, Tuscany, and Southern Italy & the Islands. Within these broad divisions, recipes are presented in the traditional manner of antipasti, primi, secondi, and dolci.

We found it slightly disconcerting that the recipes are titled and indexed in English, and only in English. After years of seeing Italian cookbooks on coffee tables and Molto Mario e amici on the Food Network, even kitchen novices are familiar with the names of dozens of Italian dishes. We actually had some trouble finding recipes we were sure would be in the cookbook. It took us a while to locate Schiacciata, Tuscan bread with grapes, which appears undercover as ‘Etruscan Grape Tart.’

Most of the recipes are uncomplicated and easily approachable by a home cook. With most, their very simplicity transmits the message that using the finest ingredients makes a difference. A quickly prepared dish from the Amalfi coast, Pasta with Walnuts and Anchovies, needs but a few spoonfuls of extra virgin olive oil to go from pleasant to ethereal. Little more than lentils and aromatic vegetables, a basic soup is similarly elevated by a finish with flavorful olive oil. A Sicilian recipe for risotto with broccoli and almonds goes from plebeian to aristocratic with the use of vialone nano rice rather than arborio.

We’re a little skeptical about a couple of recipes Ms. Willinger’s friends share with her. For example, a recipe for Mussels with Yogurt Sauce from Sardinia sounds odd, because virtually no Mediterranean culinary tradition (except French) combines shellfish with dairy products. Perhaps, though, this represents another aspect of Italy today: la cucina nuova, the new cuisine.

Of course, writing about friends requires dining with friends. That’s what much of this book is about—the pleasure of communal dining. Ms. Willinger talks with fondness about her sister, Suzanne, with whom she goes out for coffee every day. (Suzanne Heller’s watercolors—portraits, landscapes and charming renditions of vegetables—grace her sister’s book.) A recipe for Arista di Maiale, Roasted Loin of Pork is included as a tribute to her Italian husband, because it used to be his job to chop the herbs that his mother used to stuff a loin of pork. Though Ms. Willinger’s own son is grown and no longer lives at home, a recipe for the brownies made for his birthdays gets its due.

In these pages, food is always in a social context. It’s always inclusive and largely caslinga, home-cooking, far from la menu turistica. In America, it’s increasingly difficult to pull people together for a meal (We’re working late, have soccer practice, homework, second jobs…Or we’re on diets that exclude carbohydrates or fat or meat or dairy…) It seems that too often the American friends to whom you’d like to extend an invitation are too busy, too tired, overweight or allergic to something.

Meanwhile, somewhere in Florence, Faith Willinger not only waxes rhapsodic about the joys of sitting down to share food with friends, she does it.

Disclosure: Clarkson Potter sent us this book for our review.

Sushi: A Global Yen

August 16th, 2007

The Sushi Economy

Globalization and the Making of a Modern Delicacy

Sasha Issenberg

Gotham (May 3, 2007); 323 pages; $26.00

We recall our neighbor’s seven year-old son and his first attempts to fish on our Connecticut beach. When the boy reeled in a 4-inch porgie, he begged his mother to let him keep it, so she “could take it home and make sushi.”

From Japan to Jersey City, no matter how you slice it, sushi is cool. An exploration of how it got that way is the story spun by Sasha Issenberg—The Sushi Economy: Globalization and the Making of a Modern Delicacy.

Here is another book (think of Cod, Salt, Longitude…) that examines and magnifies something small (in this case, bite-sized) to the point that it seems to reach the edges of the known world.

There’s a current trend for a journalist to place one topic center stage and then plunge out—as far as the bungee cord may reach—before coming back to center for yet another jump in a different direction. The result is “radial research,” a technique that can keep an author energized. If he is as facile a writer as Mr. Issenberg, it also mesmerizes readers. John McPhee provided the model for this sort of reportage in his 1975 citrus industry profile, Oranges. Sasha Issenberg was not born until 1980, but he’s a clearly a worthy heritor of Mr. McPhee’s format.

What relationships are shared by Pacific air cargo deficits, New Age diets, declining fishing fleets, Peruvian demographics, affluent Texas techies, the Reverend Sung Myung Moon, currency exchange rates, refrigeration advances, fat-bellied tuna, and the streetscapes of contemporary Tokyo and Los Angeles?

These are just a few of the extended leaps the author takes. But unerringly, he bounces back to the center: the global tuna trade and patterns of consumption of a commodity whose prices have ranged from six cents a pound when canned as cat food, to over $150 a pound as a New Year’s gesture of Tokyo auction braggadocio.

Sushi’s global force was unleashed in the 1970’s when, after delivering countless televisions, cameras, and stereo systems to North America, Japan Airlines needed to fill the cargo holds of its 747’s for the return trip. Tuna, favored for sushi, were plentiful in the North Atlantic and their market value in North America was low. Japanese affluence as well as modern aviation and innovative refrigeration technologies enabled fresh fish from Canada to be served to Tokyo connoisseurs. Mr. Issenberg points out this irony: the antecedents of sushi lay in the ancient Japanese custom of preserving fish in barrels of rice, but the most prized component of modern sushi had become fish of uncompromising freshness. Only hours out of the water, Boston bluefin became the return passengers on JAL’s east-bound cargo planes.

Sushi, literally “vinegar-seasoned rice,” has surprisingly recent origins. The Sushi Economy presents an overview of stalls selling snacks of rice and fish in 19th century Tokyo and follows sushi as it becomes formal restaurant fare, popular with elite samurai families. We get glimpses of traditional Japanese hierarchy (sushi chefs and their apprentices, fish wholesalers and retailers). That such codified social and economic relationships developed around sushi so rapidly is noteworthy, but perhaps not surprising in Japan. In a populous country with limited resources, there have always been brakes on upward mobility. Sushi, like so many other master-apprentice trades, tended to keep its young aspirants in lengthy training, for as long as a decade.

So, sushi chefs themselves went out, like wandering samurai, gaining experience and exposure to ideas that might not have been so well received in Japan.

Among the many engaging chapters are portraits of two acclaimed sushi chefs: Nobu Matsuhisa—a native son who left Japan—and Tyson Cole—an Army brat and white American Southerner, who subjected himself to the discipline of the Japanese sushi apprentice system.

Nobu took his knives to Peru, Alaska, and Los Angeles before actor and investor Robert DeNiro lured him to New York, where Nobu-style cuisine inspired scores of lesser establishments to dabble in sushi fusion. A product of the apprentice system before he left Japan, Nobu was nonetheless open to local influences and foreign flavors like chili and olive oil. In Manhattan, he became an exemplar of that phenomenon, the celebrity chef, a guest on late-night television and the creative director of Nobu restaurants in cities and resorts around the world.

Mr. Issenberg marvels at the Lone Star spirit of Tyson Cole:

“To pick up a sushi knife outside of the traditional sushi precincts of Tokyo, or of its sushi sister city Los Angeles, is to be released from expectation and precedent. Sushi in Austin, Texas, happens to be whatever Tyson Cole decides it should be…His craft includes both reverence for tradition and rebellion against it… [and his food is a] mixture… whatever…the global economy happens to make available…”

Cole began his serious education as a sushi chef in Austin “alongside four Japanese guitar players,” because his Japanese boss and mentor sought to hire musicians and auto-mechanics for their manual dexterity. Immersed in Japanese culture at work, Cole embraced it, going on to learn Japanese from anime cartoons. His boss took him to Tokyo.

Now the owner of his own restaurant, Uchi, Cole epitomizes the creative spirit of American culinary fusion on both menu and balance sheet. He can run a spreadsheet on monthly bluefin costs and knows what percentage of that precious commodity went into two of his best-sellers: Maguro Sashimi with Goat Cheese (topped with pumpkin-seed oil) and a crunchy tuna roll with a balsamic vinegar-reduction. Meanwhile, Uchi’s staff adheres to the strict labor division of a Tokyo sushi bar.

Even though the book has a clear progression—in both chronology and complexity—a reader can dip into it at random, to read (or reread) an especially entertaining or evocative passage. In the Gloucester chapter, one can almost hear the gulls and detect the iodine scent of the sea. Sushi Economy is heady stuff, but sensual food description is not the main course. Nonetheless, one could hardly write about Japanese food and neglect aesthetics and gastronomy. So foodies get a little tasting here and there, along with some trade and restaurant gossip.

Japan’s post-WWII industrialization and fascination with American fast food yielded restaurants with conveyor belts that brought sushi back to snack-food status for the Japanese working class. Meanwhile, outside Japan, the concept of sushi as a lifestyle statement—spare, exotic, elegant—ricocheted around the globe, morphing at every port of call. Today, sushi and sushi presentation seem to be at once traditional and the essence of what constitutes the last word in dining chic.

It’s useless to bemoan or mock the existence of Moroccan couscous and crab maki, Hawaiian Spam® sushi, and the Philadelphia Roll (A seaweed-wrapped sushi roll enriched with Philadelphia® cream cheese). The Japanese themselves are toying with their “traditional” food. Gastronomic worries about authenticity seem pointless when one learns that the “classic” sushi is not so old and that a Japanese student returning home from the US opened a “New York-style” sushi bar back in Tokyo.

Like so many comestibles on which we expend discretionary funds, sushi is a statement. But it’s different from a single-malt Scotch or premier cru Bordeaux. It’s not a table at The French Laundry, Restaurant Daniel, or Le Bernardin. It’s not a chalice of Petrossian beluga.

Mr. Issenberg’s exhaustive research and insights lead him to conclude that:

“The speed with which a rapidly enriched elite takes to sushi is not a perfect index of the development of a Western-style business culture, but one could do worse in the search for such an economic indicator. Moscow marked its resurgence from a decade of post-Soviet recession with a freshly acquired taste; in late 2001, The New York Times trumpeted that, RUSSIANS, NEWLY PROSPEROUS, GO MAD FOR SUSHI—WITH MAYO, a development that the paper noted, coincided with the country’s second year of economic growth…”

“…Culturally, sushi denotes a certain type of material sophistication, a declaration that we are confidently rich enough not to be impressed by volume and refined enough to savor good things in small doses…While to afford it frequently demands the fruits of real wealth…to order sushi signifies something different about one’s participation in the globalized economy than does being fitted for a fur coat or taking a Ferrari for a test drive. More than any other food, possibly more than any other commodity, to eat sushi is to display an access to advanced trade networks, of full engagement in world commerce.”

This idealized notion leads us to ponder yet another sushi conundrum: the appearance of nigiri and maki in the most quotidian of American dining experiences, the all-you-can-eat buffet, does not seem to have sullied sushi’s profile of restraint, purity, and style.

Consumption continues to grow. Japanese restaurateur-entrepreneurs eye an expanding class of moneyed Chinese diners as Mediterranean tuna rustlers raid “ranches” established to raise more fish than can be caught in the wild. Even as economic and environmental factors cause fish prices to gyrate, sushi is keeping its cool—in no danger of losing its place as an insignia of prestige.

###

Reviewed by Holly Chase and Skip Lombardi

Tutti a Tavola…

June 5th, 2007

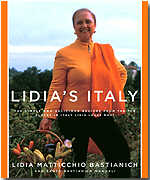

Lidia’s Italy

140 Simple and Delicious Recipes from the Ten Places in Italy Lidia Loves Most

Lidia Bastianich and Tanya Bastianich Manuali

Knopf (April 10, 2007); 384 pages; $35.00

Tutti a Tavola…a Mangiare! This Italian call to the table is familiar to anyone who’s watched Lidia Bastianich’s PBS television shows or read any of her four previous cookbooks. Now she calls us to the table again with her latest, Lidia’s Italy, written in collaboration with her daughter, Tanya Bastianich Manuali, to coincide with her most recent PBS endeavor.

The subtitle of the book, 140 Simple and Delicious Recipes from the Ten Places in Italy Lidia Loves Most, presents an idiosyncratic view of Italian cuisines. It’s no surprise to find two recipes for radicchio in the Treviso chapter, but Lidia’s Tiramisù with limoncello is an unexpected delight. In Tuscany, rather than traipsing through Florence or Siena, she takes us to the Maremma for authentic Bistecca Chianina and a sweet sage pudding. No fewer than five artichoke recipes fill the pages of her Roman chapter, but not one is the ubiquitous Carciofi alla Giudea. The Sicilian classics, Pasta alla Norma and Caponata, make their appearances in Sicily only after we’ve seen an unusual and brilliantly simple antipasto of steamed calamare.

Pellegrino Artusi began to document the regional cuisines of Italy in his self-published La Scienza in Cucina e L’Arte di Mangiar Bene, Kitchen Science, and the Art of Eating Well, in 1891. Beginning with Il Talismano della Felicità, The Talisman of Happiness, in 1928, Ada Boni began to codify these cuisines in even greater depth. The culmination of her efforts, Italian Regional Cooking, appeared in the 1960’s. Soon after, Marcella Hazan and Franco and Margaret Romagnoli began offering their own celebrations of Italy’s wonderfully diverse cuisines in print and on television.

While the menu at Lidia’s original Manhattan restaurant, Felidia continues to reflect her Istrian heritage, Lidia’s Italy affords an intimate, personal look into the cuisines and culture of ten gastronomically distinct areas of Italy. In each chapter, Lidia introduces us to the towns and countryside as we share meals in local restaurants and home kitchens with her friends and colleagues. Hers is a more focused view than we’ve had from either Artusi or Ada Boni.

Beginning in her childhood home, Istria, Lidia and crew work their way though the Italian peninsula with stops in Trieste, Friuli, Padova & Treviso, Piemonte, Maremma, Rome, Naples and Puglia with a stint in Sicily. In each place, Lidia provides a narrative on geography and climate and their significance to the cuisine. The book is liberally sprinkled with photographs taken by Lidia and her friend and fellow Istrian, Wanda Radetti. Additional, full-page photographs are by Christopher Hersheimer, who also contributed to Lidia’s Italian Table, Lidia’s Family Table, and Lidia’s Italian-American Kitchen.

Long observation has led us to the conclusion that most people salivate and do some armchair gallivanting when they get a book like this. We’ve traveled widely in Italy, so the book is a nostalgia trip for us… but we actually do cook and confess our predilection for deeply flavorful yet unpretentious dishes like Papardelle with Long-Cooked Rabbit Sugo and Marinated Winter Squash.

From the Roman chapter, we made Fettuccine with Tomato and Chicken Liver Sauce. Here, Lidia literally teaches us to concentrate. First, we reduce half a cup of white wine, then we add the soaking liquid from dried porcini and reduce that. The liquid from a can of San Marzano tomatoes is drained into the pan and simmered down, too. And if all of this reduction hasn’t been enough, Lidia invites us to “slosh some water around in the tomato can,” add it to the sauce and reduce that!Good, everyday ingredients, the elementary technique of reduction, and attentiveness yielded a superlative dish of richly nuanced flavors.

Lidia reminds her readers accustomed to supermarket displays of Chilean grapes and apricots in March, that recognition of seasonality is crucial to a grasp of Italy’s cuisines: “A trip to this market [Campo dei Fiori in Rome]—for that matter, to any market in Italy—will give you a good indication of the season, of the local flavors, and of what most of the Roman families will be having for dinner that evening.”

Or not having…

As Floridian writers, we feel disadvantaged that half the book is set in northern Italy, with corresponding recipes that call for ingredients woefully out of season here in June. We love the hearty fall and winter dishes of the north, but we just can’t get those autumnal bitter greens and root vegetables right now, because (to quote Cole Porter) “it’s too darn hot.”

Nevertheless, peppers remain in season here, so we roasted several to cook the Piemontese antipasto, Roasted Pepper Rolls Stuffed with Tuna. The stuffing, redolent of anchovies and capers, makes a delightful tuna salad in its own right, but in combination with the roasted peppers, it’s divine.

Although it didn’t seem practical for this review to prepare a dish from each of Lidia’s ten favorite places, we wanted to do at least one from the south, in part for its unconventional preparation. We chose Steamed Calamare, from Lidia’s Sicilian friend, Manfredi Barbera. Rings and tentacles of small calamare are steamed until just tender over an infusion of lemon rind and bay leaves. They are then tossed with lemon juice, grated orange rind, pepperoncino, parsley, and olive oil. The result is superb, a dish in which each component is clearly discernible and harmonious with all the others.

Lidia’s success as a restaurateur and author of four cookbooks was surely a factor in her publishers allowing her the freedom to write so engagingly. Her culinary vocabulary can be endearingly quirky: we are told to “tumble” squid and to “perk” soups… but as cooks, we know what she means.

David Nussbaum seems to have stayed close as a literary collaborator, but Lidia and her daughter, Tanya, never lose their own distinctive voices.

Tanya leads tours in Italy, and the cookbook is graced by her travel notes on some remarkable and little-known historical attractions. Mama Lidia’s words on food are always clear and encouraging. Above all, they are words of passionate conviction—that the preparation and sharing of food are among life’s most rewarding activities.

###

Reviewed by Holly Chase and Skip Lombardi

Sex, Drugs, and Olive Oil

January 9th, 2007

Alice Waters and Chez Panisse

The Romantic, Impractical, Often Eccentric, Ultimately Brilliant Making of a Food Revolution

Thomas McNamee

Penguin Press; 380 pages; $27.95.

This could happen only in America; and it could happen only once. In the late ’60’s and early ’70’s, Berkeley, California, experienced the perfect storm.

It was not literally a collision of multi-directional weather systems. Rather, the town was buffeted by winds of social change that blew everywhere and pushed a multitude of talented people into the vortex created by a charismatic young Montessori teacher who liked to cook. Alice Waters thought she’d simply like to open a little California restaurant in the tradition of the French café, a place where like-minded people could gather for good food, good wine, and good talk.

Slipping out of California in the winter of 1965 as the tensions of racial inequality and anti-war sentiments rose in America, Alice Waters went to Paris to pursue her study of 18th and 19th century French social history. Living with her American roommates where it had all happened, she was seduced by France of the 1960’s and by cuisine bourgeoise. Alice speaks of “café au lait in bowls… buckwheat crepes” I loved the idea of that restaurant, because it had those oysters out in front and “you could eat at the bar and have blanquette de veau and a glass of red wine and a basket of great bread.”

Most of all, Alice had been entranced by the culture of the café, the drama of a small stage where the lives of staff and clients were intertwined.

Returning to Berkeley seven months later, Alice and her friends rented an apartment with a good kitchen so they could cook French food. Raging campus demonstrations informed Alice’s social activism at the same time that she longed to recreate an intimate café. Alice and friends were not drawn to the barricades, but were “quietly devising a new way of living, grounded less in outrage than in pleasure, while also imbued with ideals of social justice.” One of Alice’s roommates recalls their exhilarating and frightening realization that they “didn’t have to get married” that there were “no rules,” but that they had “to make them up” themselves.

Soon, Alice had volunteered for the campaign of an anti-war congressional candidate and moved in with a radical boyfriend who also loved to cook. She plunged into the provincial French recipes and agrarian sensibilities of Elizabeth David. Julia Child was on TV, LSD was still legal, and the possibilities seemed limitless.

Author Thomas McNamee—journalist, essayist, poet, and literary critic—usually writes about the natural world. (His earlier books include The Grizzly Bear and Nature First: Keeping Our Wild Places and Wild Creatures Wild). In this undertaking, he searches for an explanation of the very recent revolution of American gastronomy. By meticulously documenting the birth and maturation of Alice Waters’ iconic restaurant, Chez Panisse, he leads us from days of 1960’s California Dreamin’ to 21st century confrontations with global agribusiness—all the while regaling us with the flirtations, foibles, and fundamental fixations of Alice Waters, her circle of friends, staff, and customers. Yet, even with so much material gathered from interviews and correspondence with living participants, we may never have all the answers.

Mr. McNamee charts the weather at Chez Panisse for over three decades: turbulence and calm, pressures high and low, updraft, downdraft, halcyon days.

Any restaurant is a complex ecosystem, and Mr. McNamee’s observational and recording skills as an environmental writer serve us well. Given nearly unfettered access to the written and oral history of Chez Panisse, he takes us up into the tree-canopy, down to the bottom of the pond, into the berry briars. And he’s an unobtrusive anthropologist—he lets inhabitants of this terrain describe themselves; we learn their quotidian routines and have glimpses of their mating dances. He trains a wide-angle lens on their rites of mourning (memorial services and fund-raisers as AIDS ripped through the Bay Area) and revelry (blowout birthday parties for the restaurant). Mr. McNamee does not simply tell us the story of the woman who defined “California Cuisine,” but the story of her whole tribe.

Though Mr. McNamee writes with clarity and erudition, his expedition notes would be enhanced by a time line and a lineage chart of la famille Panisse, as the people who drifted through Alice Water’s life came to be called.

Early on, the author himself is cautioned by one interviewee that a portrait of Chez Panisse would overwhelm him—so numerous are the players and so voluminous the material. How true!

From a psychotic mussel supplier and a brunch cook who liked to drop just a little acid, to the wordsmith who spell-checks the restaurant’s menus and the Tibetan driver of the vegetable van, the cast is operatic. As the actors step on and off the stage, we need to be reminded who they are and how they first joined the troupe.

This is especially true for the roster of chefs who revolved through (and sometimes back into) the kitchen at Chez Panisse. Each added something distinctive and many went on, as Chez Panisse alumni, to open restaurants of their own. Meanwhile, at the front of the house, Alice continued to refine the spirit of a 1930’s French café. But she was never far from the kitchen and retained her role as the final arbiter of how things should taste.

Two chefs in particular provide a telling contrast in what was happening behind the scenes and behind the stove. The mercurial Briton, Jeremiah Tower, imposed the opulence of nineteenth-century haute cuisine on the menu. Alice recounts the exhilarating, flying-trapeze preparations for Jeremiah’s Truite au bleu au Champagne (the trout leaping from the kitchen sinks before being clubbed unconscious, gutted, and immediately poached in a court bouillon—the only way to achieve that shocking blueness.)

Later, Paul Bertolli, with his Italian sensibilities, eschewed theatricality for the unmasked celebration of superior ingredients. He literally brought the menu back to earth with offerings like Rack of Lamb with Fresh Flageolet Beans, prepared for Chez Panisse’s Thirteenth Birthday Dinner.

The Chez Panisse kitchen became calmer and more professional during the Bertolli years. Most significantly, olive oil, the elixir of Alice’s beloved Provence, resumed the role usurped by Jeremiah’s butter and cream.

All the while, an unflappable, can-do attitude prevailed among the staff. Yet, it wasn’t until the arrival of Jean-Pierre Mouleé in 1975, as sous-chef to Jeremiah Tower, that Chez Panisse had an employee with any professional culinary training. This was four years after Chez Panisse’s opening night in August 1971, when dinner had included a two-hour wait between the pâté and duck courses…

What should have failed had not. But why not? From more than thirty interviews with Alice Waters herself and scores more with her friends and associates, Mr. McNamee attempts to sort and weight the factors of talent, vision, determination, romanticism, synergy, idiosyncrasy, and sheer luck.

“Unlikely” is an adjective used liberally throughout the book. It was certainly unlikely that the building which became Chez Panisse, a modest house on Shattuck Avenue, was initially leased from two lawyers– would-be investors who had pulled out at the eleventh hour, only to reappear as landlords for the enterprise. Just as unlikely was the source of initial financing: local drug dealers. Mr. McNamee is quick to point out that “These were not the scary, Glock-wielding gangsters one associates with the term drug dealer today. These were ordinary gentle Berkleyites who happened to make their livings by supplying a network of friends with pot and other soft drugs.” Alice is quick to aver that back in the ’70’s, “they were the only people who had money.”

So it was not unlikely that many of la famille would be inclined to recreational drug use—even during service. In a memorandum Alice admonished her staff against “among other potential offenses” the use of marijuana on the premises “during working hours.”

A Waters family friend reminds the author that “One of the reasons the story of Chez Panisse is so complex, is that Alice was involved with so many of the men, And if she wasn’t, then someone else in the restaurant was. Oh boy.”

“Alice?s life is driven by passion,” says a male confidant from her student days, “and sometimes she sublimates [that] in the food of Chez Panisse.”

For those who lived it, “the perfect storm” may indeed be the best analogy!

While idealism (no compromise on the integrity of ingredients) and egalitarianism (profit-sharing, right down to the dishwashers) made Chez Panisse a magnet for an endless parade of culinary aspirants, it wreaked havoc with the bottom line. Employees got travel sabbaticals and extra time to be with their families. Many helped themselves to more than an occasional bottle of Bordeaux. In the early years, food costs often exceeded the prices printed on the menus. (Alice did not want to price her Berkeley friends out of the restaurant). Even after Chez Panisse had received national acclaim, it continued to lose money as staff generously extended the extra bottle or entire meals to friends and favored clients. Managers and accountants were hired and fired—or quit in exasperation. Emotions sometimes boiled over: one disgruntled female cook punched the bookkeeper in the nose.

Eventually, the restaurant began to find its stride. What better place for forming symbiotic relationships with local providers than northern California with its year ’round growing climate? To source wild and rare ingredients, there was an official forager on staff. Traveling in France, Alice had learned the taste principle of terroir and sought local provender, organically raised, whenever possible.

Glowing reviews piled up; reservations rolled in. But seats went empty, casualties of the no-shows that plague the business. Something of a Luddite, Alice would not countenance accepting credit cards, so there was no way to recoup those losses by the standard practice top restaurants regularly employ—the no-show cancellation penalty. Chez Panisse had shareholders and a board of directors who should have overruled her. Even though Alice herself owned but a small number of shares, she was such a formidable presence in both kitchen and the front of the house that it was nearly impossible to institute change without her approval. The restaurant’s accounting was not computerized until 1984. Only in 1989, when her father (a member of the board) prevailed, were credit cards accepted.

The business of the restaurant had always been less interesting to Alice than the food itself and the human connections to that food. Mr. McNamee traces subtle shifts in the breezes following the birth of Alice’s daughter in 1983, when she began her impassioned campaign to change the way American children eat. With the success of her Edible Schoolyard project for the Berkeley public school system, Alice had a platform on which she could do much more than a Bastille Day garlic fest, and she stepped up to it in earnest. Gardening and the pleasures of communal eating were ways to educate and civilize children and the rest of our society. Organic farming and eating local products would help the planet and make us better environmental stewards.

Chez Panisse had been a college girl’s romantic dream realized, but sustainable agriculture on a global scale has since become Alice’s raison d’être.

There is a wistful irony to this, for the force of Alice?s cause now spirits her away, for weeks and months at a time, from the cocoon of Berkeley, away from la famille Panisse. She is now in her early-sixties, and her outreach and influence have become global.

Topics related to sustainable agriculture and responsible food choices grab headlines every day. Whether we merely enjoy goat cheese in our salads or volunteer to plant a community garden, Mr. McNamee makes the case that we are all the better for the efforts of the Montessori teacher who wanted a little place where one could linger to enjoy simple food and visit with friends for hours.

Reviewed by Skip Lombardi & Holly Chase