Archeology Begins at Home

August 6th, 2008Actually, at our house, archeology usually begins in the refrigerator. But yesterday, we were exploring the back of a few cupboards and chanced upon a glass jar containing approximately half a pound of very large ivory-colored beans. Even a perfunctory examination told us these were no ordinary dried pulses. Turns out they were Turkish fasulye, similar to what are known as gigantes in Spanish. While their size (about 3/4 inch in length) is more than twice the size of dried Italian cannellini, the most remarkable thing about these beans was that they were more than ten years old. Apologies for not taking a photo before we cooked them, but they were probably a cultivar of Phasoleus coccineus.

Photo by Skip Lombardi

Holly had bought them at an Istanbul street market with many Bulgarian-Turkish vendors… that was all she remembered about this batch, left from a larger stash. But, needless to say, she did remember how to cook them, even though we were not sure what the outcome would be! Nonetheless, we thought we’d see what ten year-old beans tasted like. And the truth is, they were delicious, none the worse for their vintage.

We used our standard method for cooking dried beans—our pressure-cooker. But as the beans were at least twice the size of, say, kidney beans, we gave them twice the cooking time: 20 minutes under pressure, then a three hour rest in the sealed heat of the pressure-cooker.

Since the beans came from Turkey, it seemed appropriate to turn them into a Turkish bean salad, Fasulye Pilaki, which is served alone as a light lunch or as part of an evening spread of meze.

Fasulye Pilaki

Turkish Bean Salad

Ingredients:

Olive Oil

1 Medium Onion, sliced thinly

1 Medium Carrot, sliced thinly

2 – 3 Cloves garlic, finely chopped

1 Tbs. Fresh marjoram, finely chopped (or half that amount, if using dried)

Antep pepper (Turkish chili pepper flakes which are moderately hot & sweet. Substitute Italian dried peperoncini)

1 Bay leaf

1/8 tsp ground cinnamon

1/4 Cup crushed tomatoes (canned or fresh)

1/2 Lb. dry white beans, cooked as above

Water

Salt & freshly ground black pepper

Additional olive oil

1 Scallion—green & white parts—minced

4 Tbs. Fresh mint, finely chopped

Preparation:

Heat a sauce pan (at least 1 quart) over medium-high heat. Add enough olive oil to cover the bottom of the pan, then sauté the onion, carrot, garlic, marjoram, Antep pepper, bay leaf, and cinnamon until the onion begins to wilt and the seasonings are very fragrant.

Add the crushed tomatoes, cooked beans, and enough water to barely cover the beans. Simmer the mixture, leaving the lid on the pan but slightly ajar to let steam escape. When the carrots are nearly done to your taste (we like them al dente), turn off the heat, remove the lid and let the mixture cool. Season with salt and pepper as necessary.

Serve warm or at room temperature with a splash of fruity olive oil and a sprinkling of scallions and mint. Have some good crusty bread at hand to soak up the sauce.

Serves two for lunch. More if served as one of several meze.

Peposo alla Fornicina

December 7th, 2007

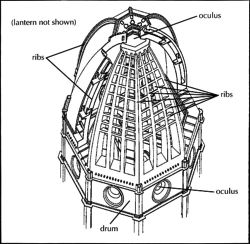

We’re in the midst of reviewing a new book on the history of the spice trade, The Taste of Conquest. Author Michael Krondl’s entertaining scholarship highlights pepper—once such a precious commodity that it was used as actual currency. This brings to mind the history of a Tuscan stew, Peposo. Numerous sources attribute its origins to the 1430’s, when the architect Filipo Brunelleschi was supervising construction of his dome on La Chiesa Santa Maria della Fiore, the famous Duomo in Florence.

The recipe is unremarkable. Then and now, it epitomizes Tuscan cuisine—local ingredients simply prepared: beef, garlic, red wine, and salt. However, one ingredient was anything but local. Giving the dish its name and distinctive bite is an unusually generous quantity of black pepper. Even more than the quantity of meat (Tuscany is famous for its Chianina beef-cattle), it was the pepper that would have made this dish deluxe in the 15th century. It is quite likely that Cosimo de Medici, art patron and the Duomo’s financier, was paying a portion of Brunelleschi’s (and perhaps even the workers’) wages in spice. The fact that medieval medicine deemed black pepper to be a “hot” and invigorating element would have been yet another reason to include it in the workers’ meals.

At the end of the work day on the Duomo, the ingredients for Peposo were sealed in a clay vessel and placed in the kiln which, during the day, had fired the terra cotta tiles for the dome. Overnight, the residual heat cooked the stew, hence its colloquial name, Peposo Notturno, Nocturnal Peposo. The following day, runners would shuttle bowls of stew up to the tile-workers on the dome. The roofers seemed to like the stew well enough, but the notion of spending their lunch hour on the dome—depriving them of the chance to play a few friendly hands of Scopa and quaff some vino on the ground—didn’t go over well at all, causing a small rebellion that may have amounted to Italy’s first labor strike.

Credit for the original Peposo recipe is claimed by nearly every town near Florence that had tile-making operations. Among those are Pistoia, Impruneta, and even La Spezia, in the province of Liguria. All these towns also insist that Dottore Brunelleschi visited each of them to select his tiles.

Over time, cooks have embellished the dish with tomatoes, mushrooms, and onions. One thing is certain: Brunelleschi’s stew could not have included tomatoes. That New World oddity didn’t appear in Italy until the mid-16th century.

By tradition, Tuscans serve Peposo over polenta or crostini, toasted bread. Contemporary Tuscans also serve peposo over mashed potatoes—another post-Columbus ingredient.

Peposo alla Fornicina

Beef Stew, Kiln-Worker’s Style

Ingredients:

2 Lb. Beef stew meat, cut into bite-sized chunks

10 Cloves garlic, peeled, but left whole

1 – 2 Tbs. Crushed black peppercorns

3 – 4 Cups dry red wine

Salt

4 Slices rustic bread (at least 1″ thick)

1 Clove garlic, peeled and halved

Preparation:

Pre-heat the oven to 250° F.

Place the meat and garlic in an ovenproof casserole. Sprinkle the crushed peppercorns over all. Add enough red wine to cover the meat by approximately one inch.

Bring the casserole to a simmer on the stove, then cover, and place the casserole in the center of the pre-heated oven. Cook, adjusting the heat so the stew barely bubbles, for approximately 6 hours. If the liquid reduces too much while the stew cooks, add hot water to compensate.

At the end of cooking, the sauce should be thick enough to coat a spoon, and the meat should be falling apart. If necessary, simmer the stew, uncovered on the stovetop, to reduce the sauce further. Taste, adding salt, as necessary.

At serving time, toast the bread slices, and rub them with the garlic halves.

To Serve:

Place one slice of the toasted bread in each of four soup bowls, then divide the stew equally among them.

Serves four.

[ad#bottom]

No Small Potatoes

November 25th, 2007

Photograph by Skip Lombardi

University of Florida sports fans, like their large reptile mascots, never hibernate. Wildlife behaviorists confirm that Gators and their supporters are active year ’round, which means they need to eat.

While we eschew artificial food coloring, we admit to a fascination with fruits and vegetables whose unusual but natural hues might scare off the the bench-warmers and Junior Varsity.

Anthocyanins, responsible for the color of hydrangeas and red autumn leaves, also give the blues to foods like heirloom varieties of corn and potatoes. And though they’ve been available for years, in farmers’ markets and as blue potato chips, antioxidant-laden blue potatoes have not been promoted with the fervor of red wine and pomegranates.

It’s a mystery to us how Gators fans have overlooked blue potatoes’ potential to boost not only their immune systems but also the profile of pre-game provender. Pairing the orange carotinoids of sweet potatoes or yams with blue potatoes makes a salad guaranteed to light-up up any tailgate party, if not the entire parking-lot.

Cooks of the Gator Nation, flaunt your colors!

Gator-Tator ® Salad

Ingredients:

1 lb Small blue potatoes (about 4 potatoes)

1 lb Small red-skin potatoes (about 4 potatoes)

1 Medium sweet potato or yam (5-6 oz.)

2 Tablespoons olive oil

1 Lime (rind and juice)

3 Tbs coarsely chopped Italian flat-leaf parsley

1/2 tsp coarsely ground black pepper

1/4 tsp Salt

1 Scallion (including green top), finely chopped

Preparation:

Wash the potatoes and yam. Place in a 3 quart saucepan and fill with enough water to just cover them. Bring to a boil and reduce to simmer for about 10 minutes.

Test a potato with the point of a sharp paring knife. The potato should feel slightly harder at the center. Drain the potatoes and set aside until they are cool enough to handle.

Meanwhile, make the dressing. Rinse the lime; grate its rind and reserve. Juice the lime into a 2-quart non-reactive bowl. Add the olive oil, parsley, salt, and pepper to the bowl. (Start with this small amount of salt so as not to obscure the delicate flavor of the sweet potato.)

You may leave the blue potatoes in their skins, but for optimum color contrast, slip the skins from the sweet potato and red potatoes. Cut potatoes into 1-inch chunks and gently combine them in the bowl with the dressing.

Just before serving, gently stir the chopped scallion into the potatoes. Taste for salt.

Serves 4-6 (recipe may be scaled up)

Because we recognize that Gainesville and the far-flung communities of the Gator Nation are multicultural, we offer the following variations.

Gator-Tator ®Salad goes ethnic…

Use the recipe above as your guideline for:

Italian: Substitute lemon rind and juice for the lime. Add 2 Tbs capers and 1 small clove of minced garlic.

German: Omit the lime; substitute 2-3 Tbs cider vinegar. Add 2 strips of cooked, crumbled bacon, 1 medium onion ( sliced and sautéed), and 2-3 Tbs freshly snipped dill.)

French: Substitute lemon rind and juice for the lime. Add 1 Tbs prepared Dijon mustard. 2 tsp snipped fresh tarragon, 1 Tbs freshly snipped chives.

Greek / Middle Eastern: Substitute lemon rind and juice for the lime. Add 2 Tbs freshly snipped mint, 1/2 cup pitted olives, & 1/2 cup crumbled feta cheese)

Indian: In addition to the lime rind and juice, add 3/4 cup yogurt, 2 Tbs freshly grated ginger, 1 minced garlic clove, 1 seeded & minced green jalapeno pepper, 2 Tbs. coarsely chopped cilantro. Adjust salt.

Latino: In addition to the lime rind and juice, add 1 tsp toasted & ground cumin, 1 minced garlic clove 1 seeded & minced green jalapeno pepper, 2 Tbs coarsely chopped cilantro. Add Tabasco or other hot sauce to taste; adjust salt.

Floridian Fusion: In addition to the lime rind and juice, add 1 cup of seeded, halved tangerine slices, 1 tsp freshly ground allspice, and several dashes of hot sauce (Pickapeppa would be terrific!)

Celebrate diversity and invent your own!

[ad#bottom]

Pasta con le Regaglie

October 25th, 2007I recently came into possession of some turkey giblets. The whole deal had an undercover quality I loved. A chef friend was preparing Turkey Divan and had no use for them. But she extended the offer, sotto voce, perhaps because she wasn’t sure if I even liked turkey giblets. Her referring to them as “body parts” added to the intrigue. I confess: this wasn’t the first time I’d been involved in a deal like this.

Years before, when I lived in Boston, my upstairs neighbor had been a cook at Jasper’s on Commercial Street. Jasper White had created a culinary niche cooking upscale versions of classic New England dishes. From time to time, my neighbor called me at work, and in a conspiratorial tone, informed me that Jasper would be making his lobster rolls that evening. I’d then make a beeline to Jasper’s at the end of my workday, sit at his small bar, and make short work of at least one of those lobster rolls, which were well worth being part of any kind of conspiracy, real or imagined. But I digress…

Though few would place turkey giblets in the same class as lobster, they too have limited availability. They are not the kind of foodstuff readily available at the local supermarket unless they come packaged in a turkey. So my little “score” was a particular treat. And for me anyway, the destiny of poultry giblets is always preordained: Pasta con le Regaglie. (reh-GAHL-yay)

In the interest of full disclosure, I confess that, for many years, my attempts at Pasta con le Regaglie have ranged from dismal failure to merely mediocre. In fact, for a long time I felt like Charlie Brown kicking that football. Each time I tried it, I knew in my heart that it was going to be great. Each time, I wound up on my back.

The problem with giblets is their inherently gristly texture—about as appealing as elastic bands. It seemed that no matter how thoroughly I dissected the giblets, or how diligent I was in removing connective tissue, I couldn’t lose the gristle.

So I spent some time studying Italian recipes; it seemed my problems related to the length of time I cooked the giblets. It turns out, this dish wants to be cooked for a long time. And my love for Pasta con le Regaglie gave me the courage to give it one more try.

The dish captivated me decades ago at a trattoria in Rome and has haunted me since. But I believe that finally, with this recipe, I’ve captured it. The giblets create an intense, rustic and earthy tomato sauce, while the livers add creamy and sophisticated depth.

Despite the fact that Caterina de’ Medici—who spent some quality time as Queen of France—is said to have enjoyed a giblet ragù with cockscombs now and then, this dish is a supreme example of la cucina dei poveri, the cooking of the poor.

Pasta con le Regaglie

Pasta with Giblets

Ingredients:

1 1/2 Lbs. Giblets (chicken or turkey)

2 Cloves garlic, peeled

1 Medium carrot, peeled and cut into chunks

1 Stalk celery, peeled and cut into chunks

1 Medium yellow onion, quartered

3 Tbs. Italian flat-leaf parsley, including stems

2 Oz. Pancetta, roughly chopped

2 Tbs. Extra-virgin olive oil

1 Cup dry white wine

1 28 Oz. Can crushed or diced Italian plum tomatoes (preferably San Marzano)

1/2 tsp. Crushed red pepper flakes

Salt & freshly ground black pepper

1 Lb. Rigatoni, or other large tubular pasta (cavatappi, penne, mostaccioli)

4 Tbs. Flat-leaf Italian parsley, finely chopped

Freshly grated Pecorino-Romano

Preparation:

Remove all connective tissue, visible fat, and silverskin from the hearts, gizzards, and livers. Chop into very fine dice and reserve.

Place the garlic, carrot, celery, onion, parsley with stems, and pancetta in the bowl of a food processor and pulse ten or more times for about one second for each pulse. The resulting mixture is known as a batutto.

Heat a four quart pot over medium heat, then add the oil. Add the batutto and cook for approximately ten minutes, until the vegetables have softened and the pancetta has rendered its fat. Lower the heat if the vegetables begin to color.

Add the giblets to the pot, and continue cooking, shaking the pot from time to time, until the giblets have lost their pinkish color.

Raise the heat to high and add the wine. Continue cooking over high heat until the wine is reduced by half.

Reduce the heat to medium-low and add the tomatoes and the red pepper flakes. Adjust heat so the sauce simmers gently; season with salt and pepper. Simmer, with the pot-lid slightly ajar, for approximately one hour, or until the sauce has thickened and any clear liquid has cooked off.

Approximately fifteen minutes before serving time, bring a large pot with salted water (at least six quarts) to the boil. Add the pasta and cook until it has just reached the al dente state. Remove from the heat and drain in a colander.

To Serve:

Divide the pasta equally among four plates and pour a ladle or two of sauce over each portion. Garnish with the remaining parsley and pass the Pecorino-Romano separately at the table.